With a little encouragement, Bryden scoured his personal archives for some trace of the high concept that never made it onto vinyl and has left barely a trace.

Apparently presented for students at a suburban high school in Whitby, Ontario, the town just west of Oshawa, Bryden recalls the degree of alienation produced by the performance. ‘We alienated them COMPLETELY. It was a very “straight” crowd and they sat or stood around the walls of the auditorium aghast, as we rolled through Black Winter and other snappy tunes’. Bryden adds that one of the band’s most avid fans at the time, Jerry Ames, came backstage after the show ‘to lecture us on the necessity for such an overwhelmingly grim piece of music’.

Bryden ties the failure of Black Winter to the fate of Lies. ‘Lies stiffed because it is was so dark. Canada wasn’t ready for anything starless and bible black – although it does end on a Tolkieneseque high note (Lord Dunsany actually). Had Christmas continued our next album would have made Lies look like Top 40. A 45-minute song about the world after nuclear war’.

The band had already used the sound of a nuclear explosion at the end of ‘The Factory’ on Lies, a two-part opus about dehumanization. The first part, ‘Where the People are Made’, describes the serial production of human life, and the second, ‘Everything’s Under Control’, a tour of the factory with statements by the foreman, district supervisor, and a smothered human being struggling for air. Invoking Irish fantasy writer Edward Plunkett’s (the aforementioned Lord --and Baron) later novels about the rise of machines, Bryden’s writing is full of highly nuanced literary and cinematic allusions, while attentively exposing the death spirals of the twentieth century. Bryden’s attachment to bleak themes was not without some sense of recovery, perhaps not resolution. In a word, his bleakness was not inexorable.

Until Black Winter, that is. Black Winter is symbolically signalled by the nuclear explosion at the end of the song, ‘The Factory’.

Digging deeper, Bryden came up with two original documents that help to shed some light on the lost work.

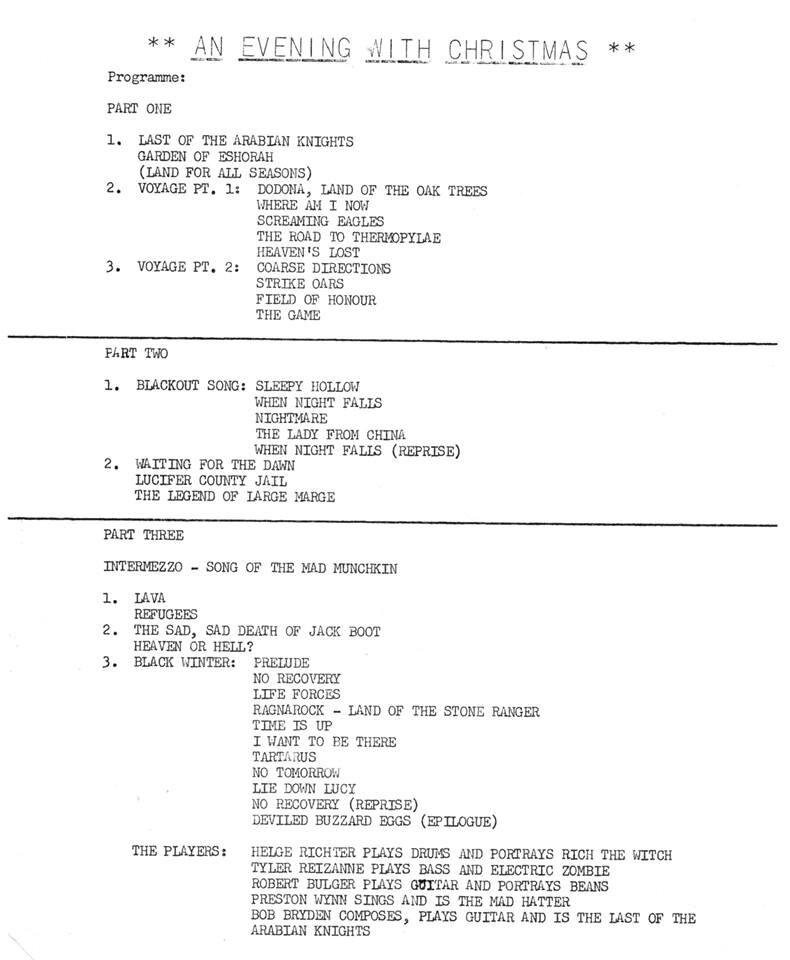

The undated programme titled ‘An Evening with Christmas’ accompanied the performance of the piece. Black Winter rounded out the third and final section of the performance. It was put together as a long-form progressive opus with a prelude, and epilogue (‘Deviled Buzzard Eggs’). It contains a reprise of the first section, ‘No Recovery’. The sections follow in order: ‘Life Forces’; ‘Ragnarock – Land of the Stone Ranger’; ‘Time Is Up’; ‘I Want to Be There’; ‘Tartarus’; ‘No Tomorrow’; and ‘Lie Down Lucy’, followed by the aforementioned reprise, and epilogue. However, the third section of the performance begins with material that was released on Lies, specifically ‘War Story’, inspired by Stanley Kubrick’s film Paths of Glory (1957) and the horrors of trench warfare in World War I.

There is more. Sometime during the 1990s, Bryden had put together all of the scraps he had in his possession from the complete Black Winter, and on a single page wrote them down for posterity. Although the opus is condensed, and it remains difficult to appreciate the overall reach of the piece, there are a few hints about what he was up to at the time.

A few of the original themes are evident, especially his use of the Norse myth of the final battle (Ragnarock) in which heroes (like Thor) meet their demise. Of course, here it is not the mighty yet imperfect god, dispatched to live among humans on earth. Rather, it is the character Lucy, and her fate on an ‘eastern’ (Saracen) road, in the surviving fragment of the chorus. And the first section, ‘No Recovery’, is perhaps the most complete, as the gloom is spread thickly in the repetition of a hopeless end of time scenario: ‘There will be no recovery … When the black winter comes…’.

There is a proto-punk sensibility in the compiled fragments of Black Winter with the exclamations of ‘no tomorrow’ that would have been out of place in early 1970s, but de riguer by the time the Pistols arrived. The imminent death of the narrator, ready to face the inexorable arrival of black winter, and join his character Lucy in a future without hope, is a grim prospect by any estimation.

The summer of love may have evaporated by 1971, but the summer of hate had not yet arrived. It wasn’t until 1977 that Johnny Rotten screeched No Future! Black Winter pointed the way towards it in an original fusion of prog and punk.

The former bassist for Christmas, Tyler Raizenne, brings the subject matter of Black Winter down to earth from its lofty metaphysical heights. He explains that the neighbourhood in Oshawa where he grew up was near an iron factory known as Fittings Foundry. ‘They used silica sand in the process and in the winter the snow around the plant would be black’. The reality of industrial Oshawa for those living there in the post-war period was sufficient to evoke a blackened winter of unchecked industrial pollution.

The search for the complete Black Winter continues.

***

All lyrics and documents are the property of Bob Bryden and used with his kind permission.